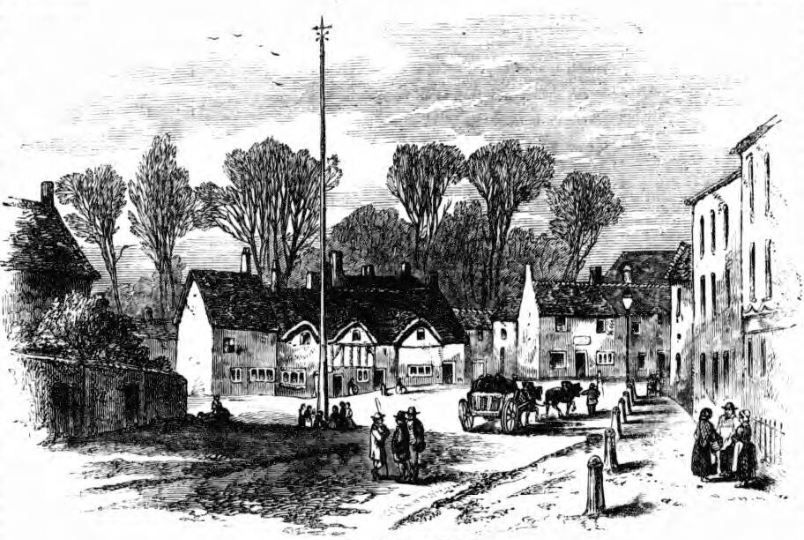

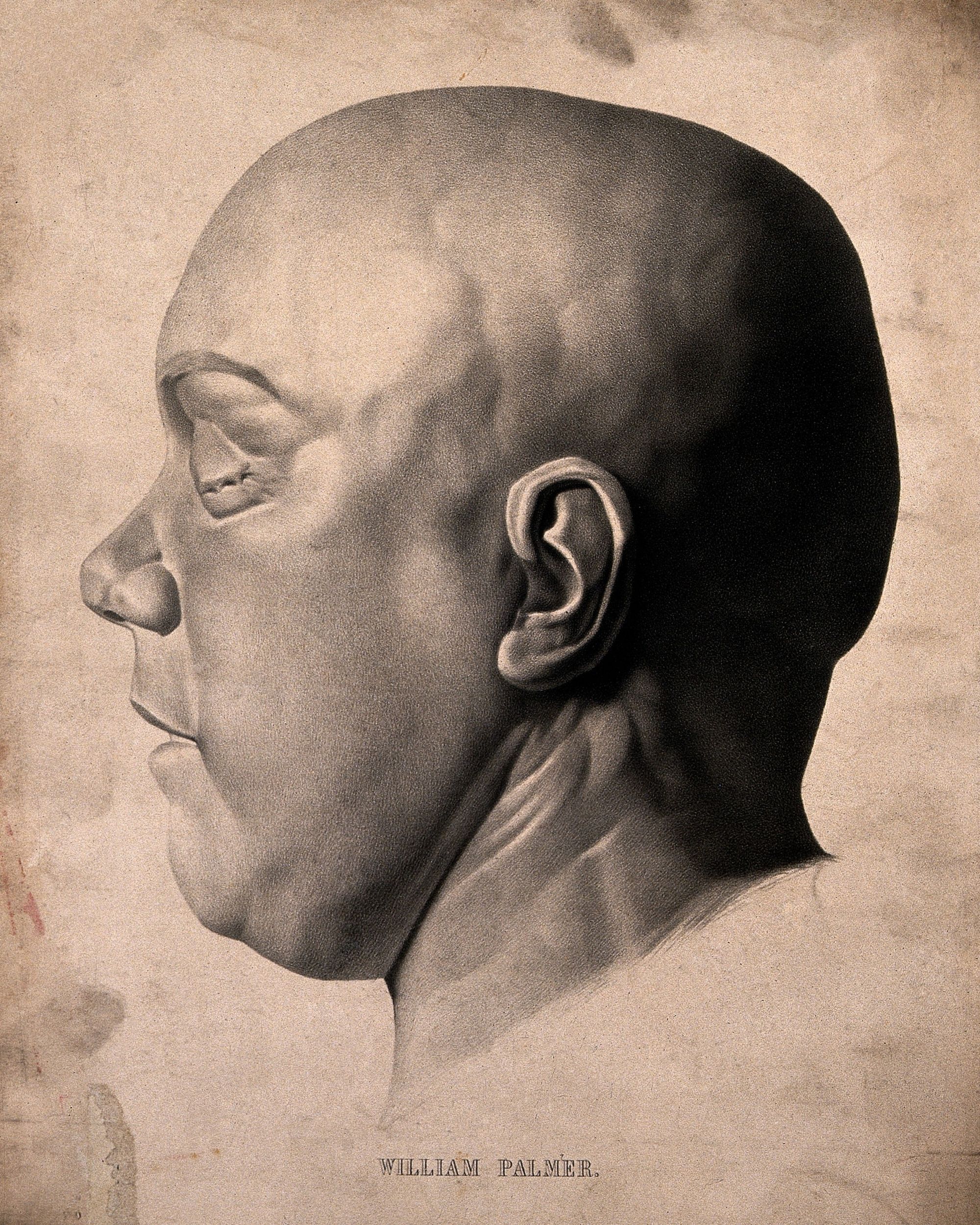

Welcome to the dark side of 19th-century Staffordshire, where crimes were committed with cunning and deadly intent. Today, we dive into the story of William Palmer, also known as the Rugeley Poisoner or the Prince of Poisoners, and one of the most notorious criminals of the era.

William Palmer was an English doctor born on August 6, 1824. His name might not ring a bell, but his actions were enough to earn him a place in history. Charles Dickens even called him "the greatest villain that ever stood in the Old Bailey". But why?

This article is part of this week's podcast which you can listen to here;

Palmer was convicted for the murder of his friend John Cook in 1855 and was executed in public by hanging the following year. The cause of death? Strychnine poisoning. Palmer was not only suspected of killing Cook but also his own family members. He lost four children to "convulsions" before their first birthdays, and his brother and mother-in-law also met untimely deaths, both suspected to have been poisoned.

Palmer was a man with a plan. He made large sums of money from the deaths of his wife and brother after collecting on life insurance policies. He also defrauded his wealthy mother out of thousands of pounds, which he subsequently lost through gambling on horses.

But what drove Palmer to commit such heinous acts? Was it greed? Was it a desire for power and control? Or was it something else entirely?

William was born in Rugeley, Staffordshire, and was the sixth of eight children. His father, Joseph Palmer, was a sawyer who passed away when William was just 12 years old. After his father's death, William's mother Sarah inherited a legacy of £70,000, which would later play a significant role in his life.

As a teenager, William worked as an apprentice at a Liverpool chemist but was dismissed after only three months due to allegations of theft. He then went on to study medicine in London, where he qualified as a physician in August 1846.

Following his studies, William returned to Staffordshire, where he met plumber and glazier George Abley at the Lamb and Flag public house in Little Haywood. After challenging George to a drinking contest, George was carried home an hour later and died in bed that evening. Although nothing was ever proven, locals noted that William had an interest in George's attractive wife.

William married Ann Thornton, also known as Brookes, on 7 October 1847, in St. Nicholas Church, Abbots Bromley. Ann's mother had inherited a fortune of £8,000 after Colonel Brookes committed suicide in 1834, and she was known to have lent William money. Unfortunately, Ann's mother died just two weeks after coming to stay with William, and her death was recorded as apoplexy.

William's interest in horse racing grew, and he borrowed £600 from Leonard Bladen, whom he had met at the races. Leonard died in agony at William's house on 10 May 1850, and his death certificate listed William as "present at the death." The cause of death was recorded as "injury of the hip joint, 5 or 6 months; abscess in the pelvis." Despite having recently won a large sum of money at the races, Leonard had little money on him at the time of his death, and his betting books were missing.

These were just the first of many suspicious deaths that would occur in William Palmer's life.

His financial troubles began to pile up after he married his wife, Ann. The couple had five children, but sadly, only their firstborn son, William, survived to adulthood. The rest of their children died of convulsions in infancy, and at the time, their deaths were not viewed as suspicious.

However, as Palmer's debts grew, he began to take out life insurance policies on his loved ones, including his wife. When Ann died of cholera in 1854, Palmer received a payout of £13,000 from the insurance company. But his debts continued to mount, and he attempted to take out a massive £84,000 insurance policy on his brother, Walter.

Walter's drinking problem soon led to his demise, but the insurance company refused to pay out the policy. They sent inspectors to investigate, and they found that Palmer had also been trying to take out an insurance policy on the life of a farmer under his employment. The company refused to pay out on his brother's death and recommended a further investigation.

With his life spiralling out of control, Palmer became involved in an affair with his housemaid, Eliza Tharme, who became pregnant with his illegitimate child. Palmer's financial troubles were growing, and he began to plan the murder of his former friend, John Cook.

John Parsons Cook was a wealthy young man, inheriting a fortune of £12,000. He loved the thrill of gambling and was friends with William Palmer, a fellow gambler. The two attended the Shrewsbury Handicap Stakes in November 1855, where Cook won £3,000 by betting on "Polestar," while Palmer lost heavily by betting on "the Chicken."

After the race, the pair celebrated at a local drinking establishment, the Raven. However, Cook soon fell ill, complaining that his gin had burnt his throat. Palmer made a scene, insisting that there was nothing wrong with Cook's glass. But Cook was violently sick, suspecting that Palmer had dosed him.

Cook returned to Rugeley and booked a room at the Talbot Arms, where he met with Palmer again. Palmer took responsibility for Cook's well-being, and Cook's solicitor sent over a bottle of gin. A chambermaid took a sip of the gin and fell ill, while Cook's vomiting became worse.

Palmer began collecting Cook’s bets, he collected a total of £1200. He then went to Dr Salt's surgery and purchased three grains of Srychnine and put them into two pills, which he administered to Cook. On November 21st, Cook died in agony, screaming that he was suffocating.

Cook's stepfather arrived to represent the family, and Palmer informed him that Cook had lost his betting books, which were of no use as all bets were cancelled once the gambler had died. Palmer obtained a death certificate listing the cause of death as 'apoplexy.'

A post-mortem examination took place, overseen by Dr Harland, medical student Charles Devonshire, and assistant Charles Newton. Palmer interfered with the examination, taking the stomach contents off in a jar for 'safe keeping.' The jars were sent off to Alfred Swaine Taylor, who complained that the samples were of poor quality.

Palmer also wrote to the coroner himself, requesting that the verdict of death be given as natural causes, enclosing a £10 note. Taylor found no evidence of poison but still believed that Cook had been poisoned. The jury at the inquest delivered their verdict, stating that Cook was poisoned by Palmer.

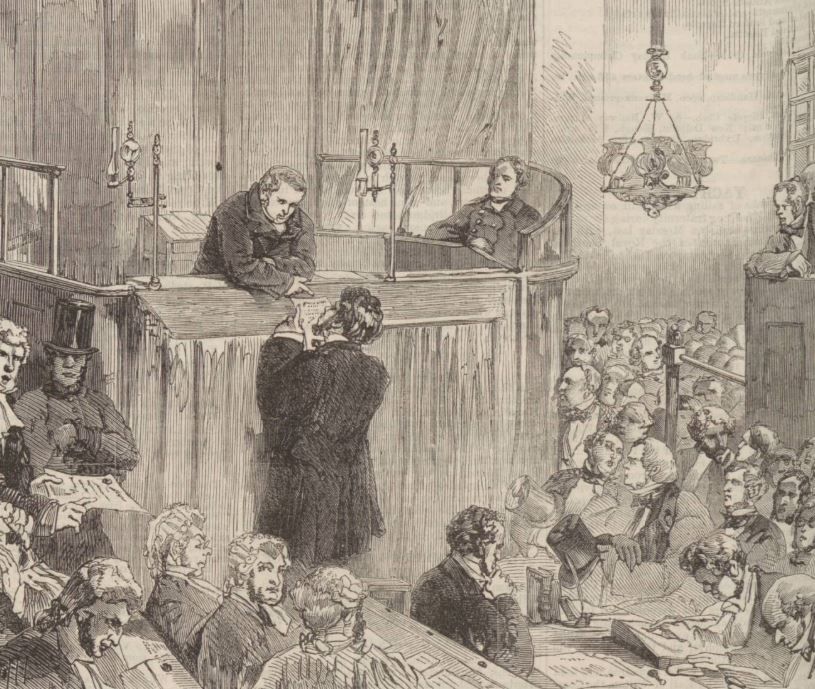

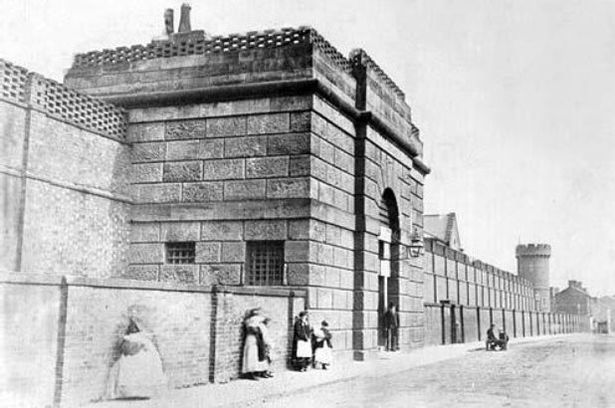

Palmer was detained at Stafford Gaol after a creditor reported suspicions of him forging his mother's signature. He threatened to go on a hunger strike but backed down after being informed that he would be force-fed. An Act of Parliament was passed to move his trial to the Old Bailey in London, as it was deemed impossible to find a fair jury in Staffordshire where local newspapers had printed detailed accounts of the case and the deaths of Palmer's children. However, some people believe that the trial was moved for political reasons to secure a guilty verdict.

The Home Secretary ordered the exhumation and re-examination of the bodies of Walter and Ann. The organs of Ann's body were found to contain antimony, but Walter's body was too badly decomposed.

Palmer's defence was led by Mr Serjeant William Shee, who faced criticism from the judge for telling the jury that he personally believed Palmer to be innocent. The prosecution team, on the other hand, proved to be forceful advocates, demolishing the defence witness Jeremiah Smith's testimony. Circumstantial evidence came to light, including eyewitness accounts of Palmer purchasing strychnine and chemists admitting to selling him the poison without recording it in their books as required by law.

During the trial, Palmer's financial circumstances were elaborated upon. Thomas Pratt, a moneylender, testified that he had loaned money to Palmer at a staggering interest rate of 60%. Additionally, the bank manager verified that Palmer had £9 in his bank account.

The cause of Cook's death was hotly disputed, with medical witnesses on each side bringing their testimony. The cause of death was determined by the prosecution witnesses, including Alfred Swaine Taylor, to be "tetanus due to strychnine." However, the defence called upon fifteen medical witnesses who contended that the poison could not have been the cause because it should have been found in the stomach.

After deliberating for just over an hour, the jury found Palmer guilty. Lord Campbell handed down a death sentence, which Palmer received without any reaction.

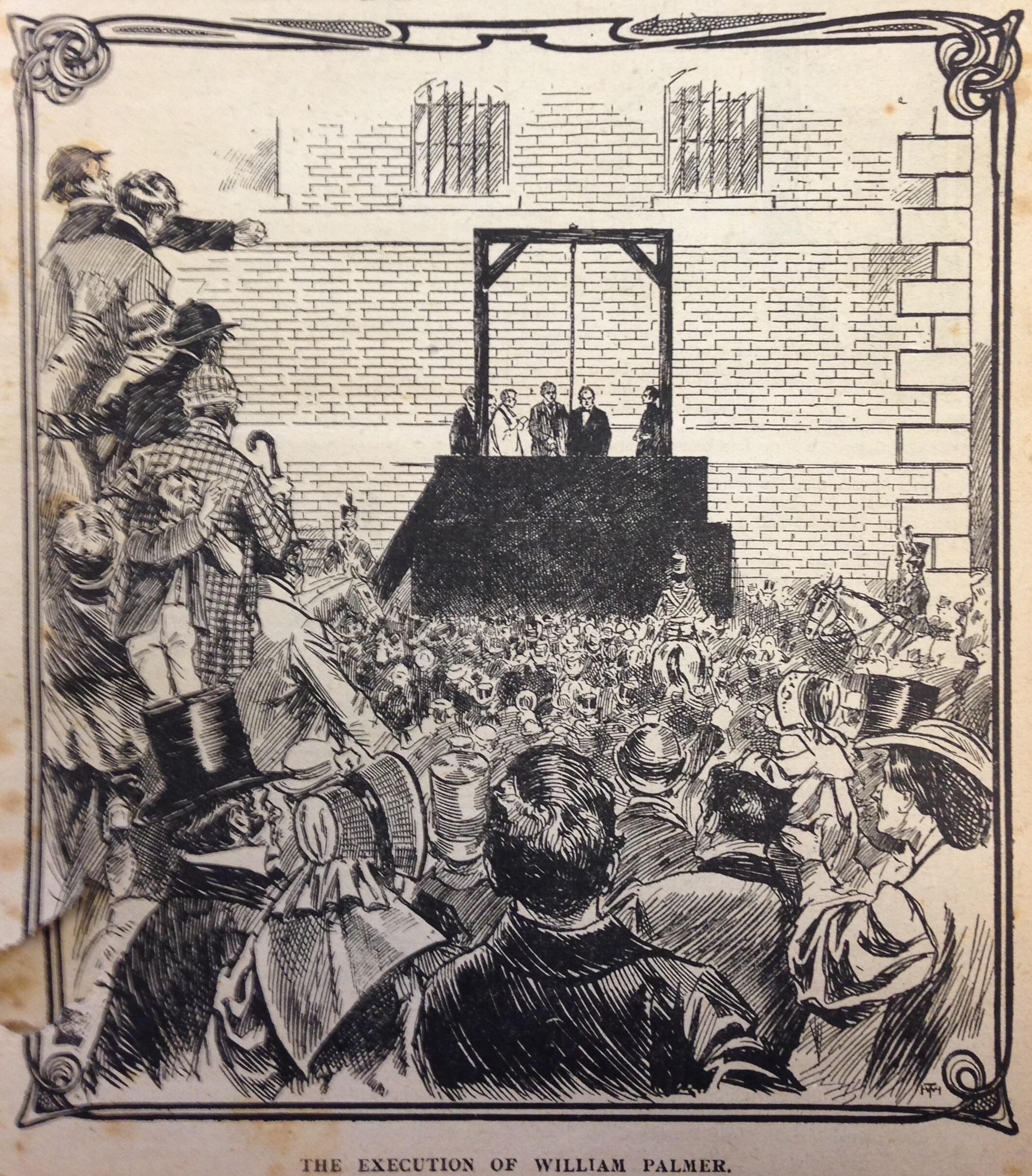

George Smith carried out the public hanging of William Palmer on June 14, 1856, at Stafford Prison in the presence of a crowd of around 30,000 spectators. As he stepped onto the gallows, Palmer reportedly looked at the trapdoor and exclaimed, "Are you sure it's safe?"

Before his execution, the prison governor asked Palmer to confess his guilt, which led to an interesting exchange of words.

Palmer: "Cook did not die from strychnine."

Governor: "This is no time for quibbling – did you, or did you not, kill Cook?"

Palmer: "The Lord Chief Justice summed up for poisoning by strychnine."

Despite his denial, Palmer was hanged and buried beside the prison chapel in a grave filled with quicklime. After the execution, his mother reportedly said, "They have hanged my saintly Billy."

But the story doesn't end there. Shortly after the execution, a newspaper reported that the rope used to hang Palmer was being sold as an "interesting relic" in Scotland and was meeting with ready purchasers. The rope was reportedly selling for five shillings per inch.

Some scholars believe that the evidence presented at the trial should not have been enough to convict Palmer and that the judge's summing up was prejudicial. However, in 1946, a final piece of evidence was found that could have sealed Palmer's fate: a prescription for opium written in his own handwriting, on the reverse of which was a chemist's bill for 10 pence worth of strychnine and opium.

Thank you for reading!

If you like what you have read, please feel free to support me by following and signing up for my newsletter and/or buying me a coffee!

Thank you.

I use the British Newspaper Archive to help with my research and you can sign up for a free trial here.

If you are interested in your local and family history, you can sign up for a free trial of Find my Past and access all archived local records and find your past.

If you are interested in the history of William Palmer then check out these books on Amazon.

His life story has even been made into film! - https://amzn.to/3LWAMAU

Check out my recommended reading list